How did Neanderthals grow? Does modern man develop in the same way as Homo neanderthalensis did? How does the size of the brain affect the development of the body? A study led by the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) researcher, Antonio Rosas, has studied the fossil remains of a Neanderthal child's skeleton in order to establish whether there are differences between the growth of Neanderthals and that of sapiens.

|

| Neanderthal children may have grown up as slowly as modern humans [Credit: © S.Plailly, E.Daynes/LookatSciences] |

"Discerning the differences and similarities in growth patterns between Neanderthals and modern humans helps us better define our own history. Modern humans and Neanderthals emerged from a common recent ancestor, and this is manifested in a similar overall growth rate," explains CSIC researcher, Antonio Rosas, from Spain's National Natural Science Museum (MNCN). As fellow CSIC researcher Luis Ríos highlights, "Applying paediatric growth assessment methods, this Neanderthal child is no different to a modern-day child." The pattern of vertebral maturation and brain growth, as well as energy constraints during development, may have marked the anatomical shape of Neanderthals.

Neanderthals had a greater cranial capacity than today's humans. Neanderthal adults had an intracranial volume of 1,520 cubic centimetres, while that of modern adult man is 1,195 cubic centimetres. That of the Neanderthal child in the study had reached 1,330 cubic centimetres at the time of his death, in other words, 87.5% of the total reached at eight years of age. At that age, the development of a modern-day child's cranial capacity has already been fully completed.

"Developing a large brain involves significant energy expenditure and, consequently, this hinders the growth of other parts of the body. In sapiens, the development of the brain during childhood has a high energetic cost and, as a result, the development of the rest of the body slows down," Rosas explains.

Neanderthals and sapiens

The cost, in terms of energy, of anatomical growth of the modern brain is unusually high, especially during breastfeeding and during infancy, and this seems to require a slowing down of body growth. The growth and development of this juvenile Neanderthal matches the typical characteristics of human ontogeny, where there is a slow anatomical growth between weaning and puberty. This could compensate for the immense energy cost of developing such a large brain.

|

| Skeleton of the Neanderthal boy recovered from the El Sidrón cave (Asturias, Spain) [Credit: Paleoanthropology Group MNCN-CSIC] |

The only divergent aspect in the growth of both species is the moment of maturation of the vertebral column. In all hominids, the cartilaginous joints of the middle thoracic vertebrae and the atlas are the last to fuse, but in this Neanderthal, fusion occurred about two years later than in modern humans.

"The delay of this fusion in the vertebral column may indicate that Neanderthals had a decoupling of certain aspects in the transition from infancy to the juvenile phase. Although the implications are unknown, this feature could be related to the characteristic enlarged shape of the Neanderthal torso, or slower brain growth," says Rosas.

The Neanderthal child

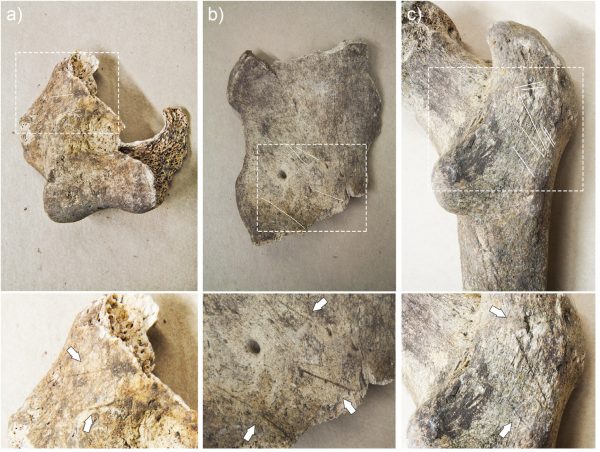

The protagonist of this study was 7.7 years old, weighed 26 kilos and measured 111 centimetres at the time of death. Although the genetic analyses failed to confirm the child's sex, the canine teeth and the sturdiness of the bones showed that it to be a male. 138 pieces, 30 of them teeth (including some milk teeth), and part of the skeleton- including some fragments of the skull from the individual- identified as El Sidrón J1, have recovered.

|

| (Left to Right) Antonio García-Tabernero, Antonio Rosas and Luis Ríos beside the Neanderthal child's skeleton [Credit: Andrés Díaz-CSIC Communications Department] |

Discovered in 1994, the El Sidrón cave, located in Piloña (in Asturias, northern Spain) has provided the best collection of Neanderthals that exists on the Iberian Peninsula. The team has recovered the remains of 13 individuals from the cave. The group consisted of seven adults (four women and three men), three teenagers and three younger children.

Previous studies have been carried out by a multidisciplinary team led by the paleoanthropologist Antonio Rosas (CSIC's National Museum of Natural Sciences), the geneticist Carles Lalueza-Fox (Institute of Evolutionary Biology, run by CSIC and the Pompeu Fabra University) and by the archaeologist Marco de la Rasilla (University of Oviedo).

Source: Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) [September 22, 2017]